May 19, 2015

There might have been a disjoint between Twitter and real life in terms of public opinion around the recent General Election (see last week’s blog), but Twitter offered a fascinating journal of what the politicians were thinking in the final days of the month-long campaign.

It was supposed to be the closest-run UK General Election in a generation and was predicted to result in a hung parliament. Yet no hanging took place, and eventually the excited crowds dispersed for another five years.

So what went wrong? This may have been the second Twitter UK election in terms of politicians but the majority of voters still aren’t following British politicians. Nevertheless, political despatches on Twitter perhaps revealed more about respective politician’s chances of winning the election than any number of Question Time sessions beside the House of Commons despatch box.

The swing to the Conservatives was only 0.8% and to Labour 1.5%. However, the largest party in Westminster in 2010, the Conservatives, extended their lead by enough to secure the first majority government in Britain in five years on 7 May.

We’ve taken a look at the final week of campaigning to see some glaring differences in the tweets and messages being conveyed by the two men most likely to be Prime Minister: David Cameron of the Conservatives and Ed Miliband of the Labour Party.

State of the Twitter accounts

Firstly, let’s take a look at the status of the armour.

Cameron had 961,000 followers on 7 April, exactly a month before the election. See more in an earlier blog UK Election: Twitter wot won it for…?

Miliband had less than half as many followers in April, at 418,000.

Campaigning did boost followers, with Cameron securing a total of 1.06m days after the election, while Miliband peaked at 511,000. In the ten days since the election, Cameron has continued to tweet and retain followers, while Miliband, who quit as party leader the day after the election result and has failed to tweet since 8 May, has slipped to 510,000 followers.

Secondly, let’s look at who was most prolific using Twitter before and during the campaign. Cameron, a late convert to Twitter who only set up an account in January 2010, has as of this week tweeted 1,847 times. Miliband, on the other hand, has used Twitter since July 2009, giving him a six-month advantage, and has tweeted 4,745 times. Hands down Miliband won that round.

It’s all in the message

Finally, what about the all-important messages both party leaders conveyed?

It is often said you win elections when you appeal to voters’ aspirations, and lose them when you defend privileges.

That was wisdom not lost on Cameron, who used both aspiration and fear as his two weapons to undermine support for Labour.

Cameron regularly warned of the “chaos” of Miliband forming a coalition with the Scottish nationalists and insisted that only he could be trusted to protect economic stability in Britain.

But Cameron also made an earnest push in the final days of the campaign to appeal to aspirations. Any government still reeling from the effects of an economic crisis has an uphill struggle to win over voters, so the message is more important than even its mode of transport.

Cameron’s campaign team were adept at ensuring that he played back the achievements he had won for working people.

For example, on 6 May Cameron tweeted that 37,000 Asda staff (not all in the Kingswood, Surrey branch it has to be clarified!) benefited from tax cuts since 2010.

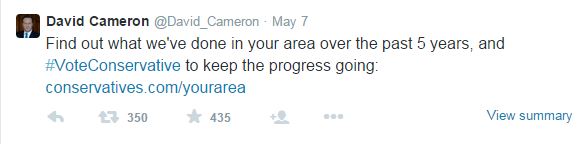

On election day, Cameron also fired off a tweet linking to an online calculator that claimed to show what his government had achieved in the past five years. It was a message of achievement and continued prosperity.

Cameron managed to inject more original content into tweets between 3 May and polling on 7 May than Miliband. Cameron used a lot more “doorstepping” photos and anecdotes.

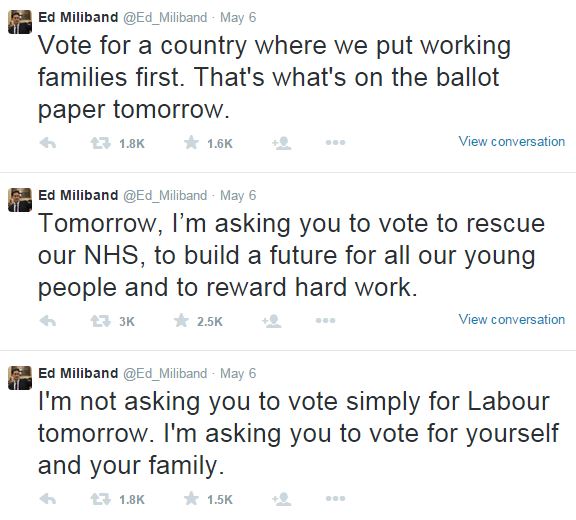

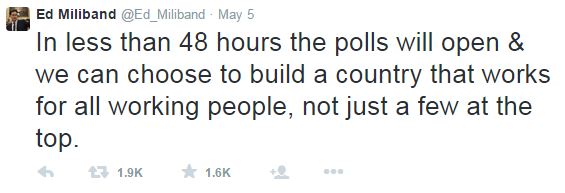

The Labour leader’s tweets largely comprised of slogans, often without images, which were played back repetitively several times in the past few days such as this one:

While busy with all that, he also failed to capitalise on the key to success: aspirations. It was the politics of fear, such as the loss of the NHS, or the Old Labour strategy of complaining about the privileges of the rich and powerful.

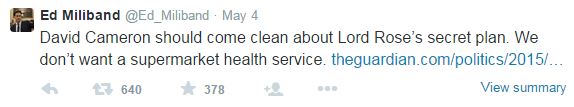

There were also the rather specific and unclear allegations about individuals. If you work in the health sector, you would know who Lord Rose is and you might know his “secret plan”. For the rest of us, this was too vague to impress.

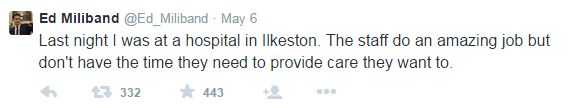

On 6 May, Miliband tweeted praise for hospital staff in Ilkeston, but rather than explain what he plans to do to make their amazing jobs better, he complained about how things were now.

So how did the messages translate with the voters?

According to the “Battleground Britain” project voters were asked to keep a diary of their political thoughts during the campaign. The project, carried out by Deborah Mattinson of Britain Thinks in association with The Guardian newspaper, found that the key words which rose in prominence for Cameron during the campaign were “confident”, “repetitive”, “smooth” and “statesman”.

For Miliband the clutch of words gaining prominence included “principled”, and “determined”, but negatively also “awkward”, “untrustworthy” and “trying”.

You can download the report here.

Road to improvement

But there was a wobble for the Prime Minister. By April, Cameron hadn’t replied to a single tweet all year. According to Twitonomy only 1% of his tweets were replies and 5% of his tweets were RTs which tells us he doesn’t interact much with other users or other users’ content. For Miliband it was better news: he interacted more with his audience with 8% of his tweets being replies and he also shared other peoples’ content more with 21% of his tweets being RTs.

Twitter’s own research suggests that adding photos into political tweets increases retweets by 62% and adding videos by 14%. In the final week Miliband’s tweets were mostly just text.

If both party leaders at the time of the 2020 General Election sharpen up the delivery of aspirational policies in both social and traditional media, there is a greater chance of a close-run election actually happening.